When you ask 11-year-old Willie Rates about life with Asperger’s he seems comfortable with his place in the world, both figuratively and literally. “Well, you’re indeed not usual, which I’m perfectly ok with. It’s like I’m Portland unusual, or Los Angeles unusual.” A lover of ancient Egypt & Rome, dinosaurs, and Playmobil figures, Willie will tell you that first and foremost he is a filmmaker, with exactly 123 movies to his credit.

He lives in Portland, Oregon with his Mother Tobi, Father Dale, and his 7-year-old brother Jacob, who is also on the Autism spectrum. It was more than two years ago that Willie first donned his now trademark Nemes, a striped headcloth worn by pharaohs in ancient Egypt. The remnants of a Halloween costume, it is a visual reminder of his obsession with Ancient Egypt.

Willie morphed his interests in ancient Egypt and dinosaurs to create his own, the Phananosaraptorosaurus (Species: Marinus Subspecies: Domesticus) which he imitates by walking on his hands at home and in public. “I remember right before fifth grade, Willie asked me if he had to walk bipedally at school or if he could walk quadrupedally,” says his mother.

An avid stop motion filmmaker, Willie movie's are distributed through his production company, KhAnubis Productions. His film topics usually center on ancient Rome and Egypt, with Playmobil figures or stuffed animals taking the starring roles. His latest piece, Dr. Tyrannus’ Revenge, is complete with German Subtitles.

Like many preadolescents, Willie reluctantly does a little grooming before school. Though Tobi and Dale are not on the autism spectrum, Tobi has a twin sister who children are, laying credence to the generally accepted belief that autism is a genetic disorder. Tobi agrees, “I would say for me and Dale, we’re not autistic, but we definitely see similarities in ourselves, just not enough to make a diagnosis. Though,” she jokes, “usually if your kid’s been diagnosed, you should probably get a diagnosis yourself!” The truth is, there is no one certain cause for autism because autism is not a medical condition. Instead, it is a definition given to those that exhibit a specific set of behaviors.

“In comparison to my last school, it’s a paradise,” says Willie. “You can customize your own schedule, you actually get to say whatever you want. They’re much nicer at Pacific Crest and there are a lot less kids so I don’t have to make as much friends to be popular at the school. I now think I’m the kind of guy who has a lot of friends."

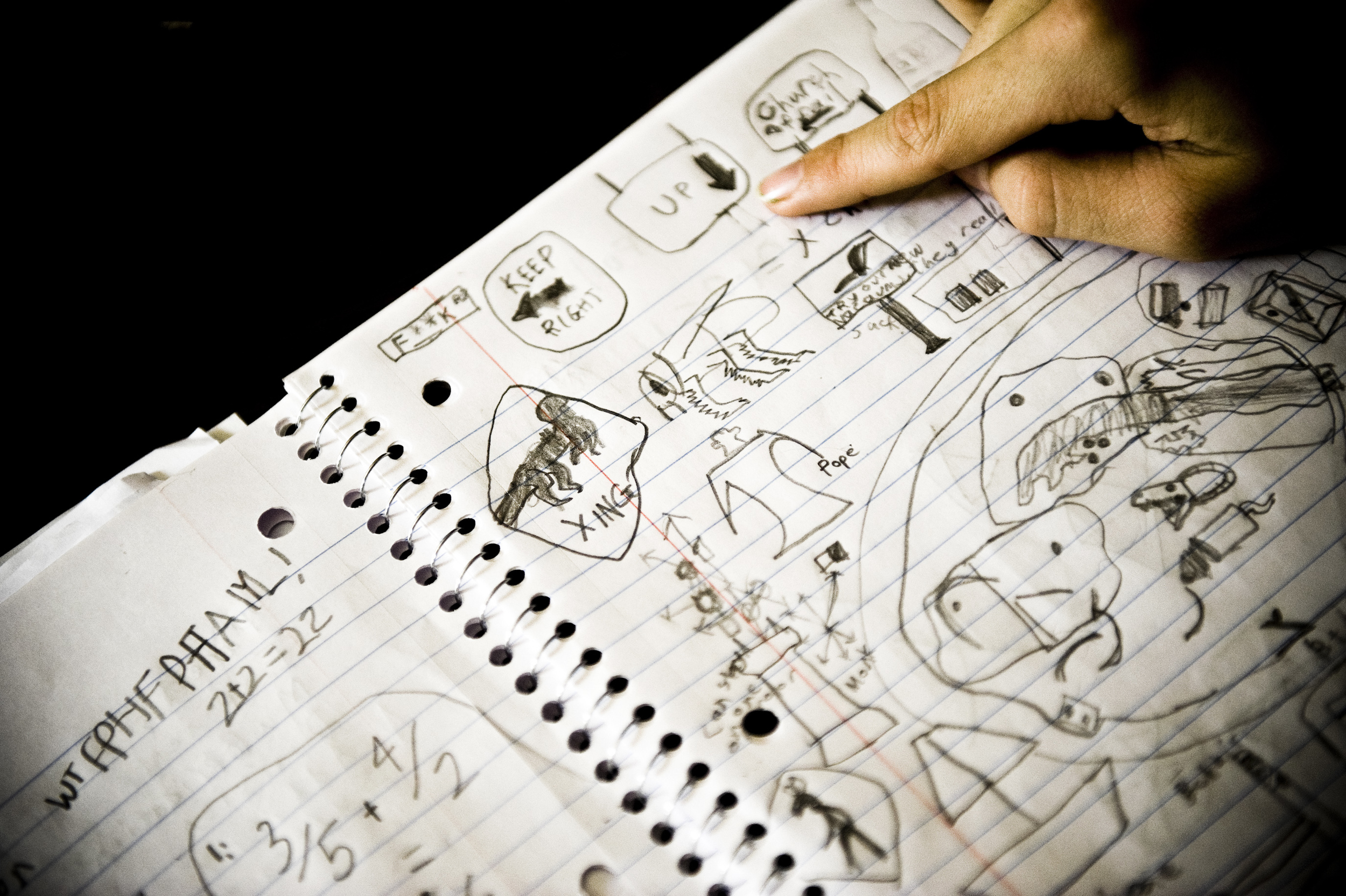

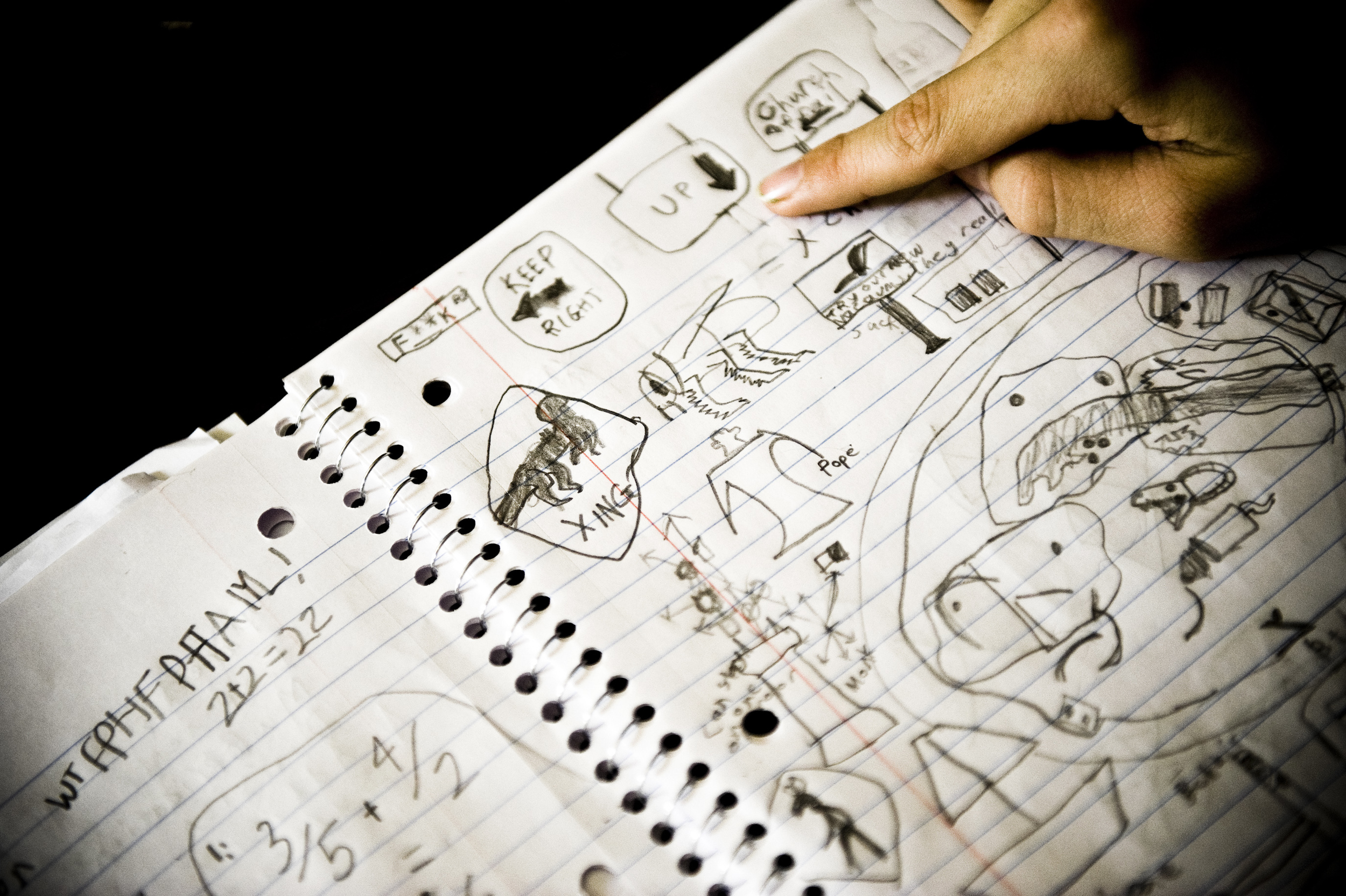

During math class, Willie’s notebook fills up with drawings rather than equations. In general his relationship with school is uneven, with him excelling in topics that fascinate him. Like many people that have Asperger’s, Willie can spend hours fixated on very specific topics or interests, which is why many with the diagnosis make good lawyers or computer programmers. “To us, Willie was our first child, the quirks we noticed with him, we just thought he was a genius. But the teacher at the preschool we went to, she suggested we get him evaluated,” say his mother.

Here, Willie creates a movie set.

Willie attempts to play with his brother Jacob. Jacob is profoundly autistic and for the most part, nonverbal, though he can sign some words.

His father, Dale, marvels at the changes time has brought, “In my day, in the 60’s, there was one description, or two descriptions really, retarded or normal. And you didn’t want to be retarded. Now it’s not a shame. It’s everywhere. We’re all a little weird everywhere you look. Everyone’s got a quirk, or a strange little thing. And that’s ok, that’s what makes us unique. Otherwise we’re just robots and rocks.”

We’re a happy group here,” says Dale. “We have group hugs, actually we have a family hug time. I mean it’s not like it’s scheduled, it just happens. Very few things are scheduled around here actually.”

First tested for Autism at age 4, Willie’s path to a diagnosis hasn’t been a straightforward one, “First we were told, we don’t what, but there is something going on here,” says his father. “And that turned into Autism and that sort of started becoming Asperger's and then it became…who knows he might just be a really unique guy.”

E.A. is a mother, wife, ballet dancer, public speaker, and self advocate. She says that she has spent most of her life pretending to be normal. “Nothing has come naturally to me other than my intuition. But everything else I do, my mannerisms, the way that I talk, the faces that I make, the things that I do, how I do them have all had to be learned and have all had to run through my internal editor. This is so that they can be compatible with what I am showing or what I am doing so that I am not detected by the citizens of this world as different.”

"In my next life I want to be born messy!" laughs E.A. as she picks up leaves off her yard one by one.

"To be misunderstood is extremely frustrating and it happens to me on a daily basis. I’m frustrated that I have to do this on a daily basis and then field off questions like, ‘But you seem so normal’ or ‘You seem fine.'"

“I have a certain way that I get ready every day. If I’m going to clean my house, there is a certain way it needs to be clean and a certain way it needs to be done. The was I do it is very scripted because that is the only way I know how to do it.” People with Asperger's are often comforted by routine.

E.A. says she often has difficulty reading facial expressions and social situations, a trait common in Asperger's. This is true even for her husband and children.

E.A.'s youngest son is on the autism spectrum and she works hard to make sure he doesn't make the same mistakes she did, often correcting his behavior. "That’s what I’m looking for, to help him increase his recovery time, between upsets, as quickly as possible, so that the damage to self-esteem is minimized."

E.A. is the Community Council Chair and Research Assistant at Academic Autistic Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE). She also does a lot of work with disabilty rights, “My goal in public speaking and advocacy work is to bring a sense of reality into the picture, a sense of first hand experience, and hopefully, a large sense of truth.”

E.A. has a cochlear implant and hearing aid and says that in some ways it has been a blessing in disguise because she is so sensitive to noise.

“When I was younger I would decide somebody was my friend and that was it in my head, we were friends and we didn’t have to go through all those formalities and rules that I didn’t even know existed. So I would be way too forward and come on way too strong and just be so hurt when this person didn’t want to be my friend."

E.A. finds solace in one of her passions, ballet, and will spend hours at practice. “What I like about dance is that it is a form of expression without having to speak. Things might be stressful at work or certain things could be happening in life, but there’s always ballet class, there’s always that barre, and that leotard and those tights that I put on. And when I go in there my mind goes to a completely different place and it becomes a form of expression where I am not having to speak or interpret anything...as long as I can get the choreography down!”

“I don’t need to be fixed and I don’t need to be cured and I wouldn’t want to be fixed or cured. I want to be accommodated, I want to be respected and I want to be understood.”

"When I was younger I wasn't always accepting of myself and I wanted to be normal. A lot of times I look at other people and I think, I wish I could be that person," say Anna Bauer who lives with her mother Mary. Diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome, Anna had a difficult childhood, often bullied for being different. Now 22-years-old, her mother Mary is not sure what lies ahead for her daughter who has never had a job and still lives at home.

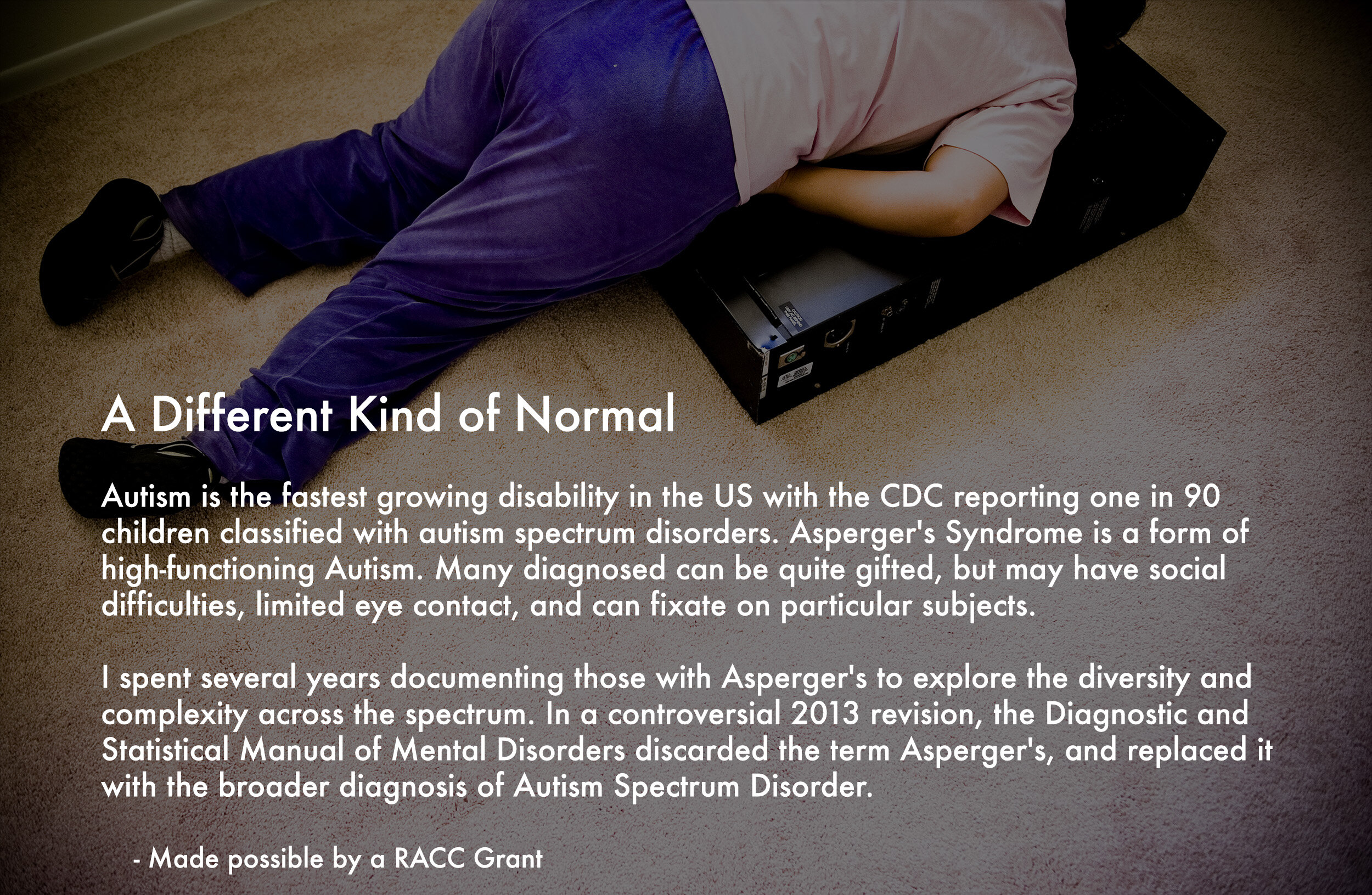

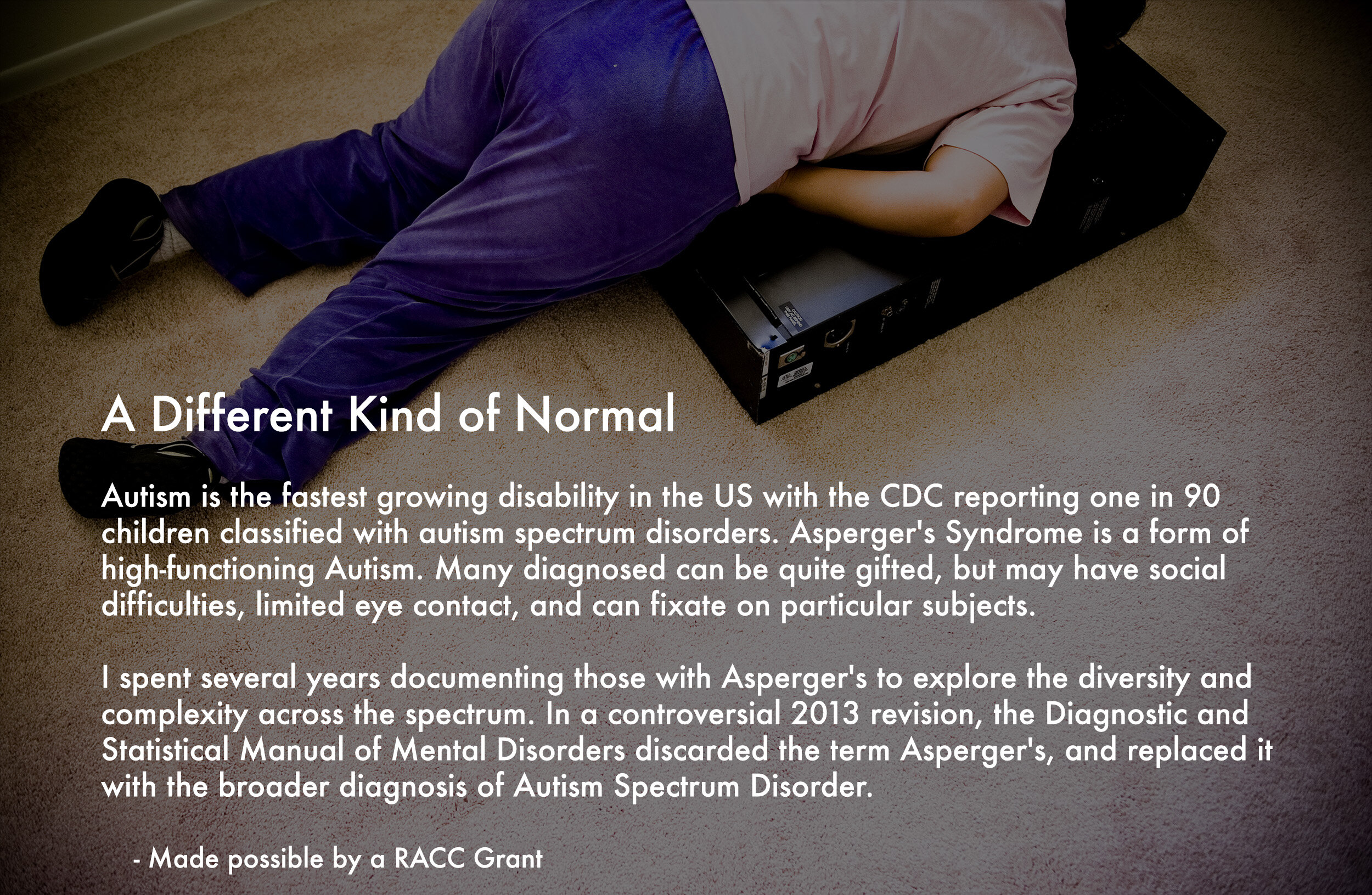

After a stressful move from her childhood home, Anna Bauer lays on her prized possession, a 24-second shot clock, to comfort herself. Because of her Asperger's Anna has a tendency to fixate on certain subjects or objects. For her it is scoreboards, roller coasters, and most importantly, shot clocks, of which purchased two on ebay for around $700.

Anna moves her 30-pound shot clock. When she and her mother go on road trips the shot clock comes with and Anna now has planned a visit to University of California, Berkeley to visit the scoreboard they have there. "Ever since I go this shot clock, especially when I am home alone, I feel less lonely and I feel like it is another friend to me and it actually gives me company," say Anna.

Anna volunteers as a scoreboard operator at the Beaverton Hoop and last year received the volunteer of the year award. Originally fascinated with gym floors, she would lie on for hours. Now she moved on to score boards and dreams of being a professional score keeper.

Anna started attending the local community Church, much to the surprise of her Atheist mother. "I like going to church," say Anna. "Where it is peaceful and positive, and the people there are really nice."

For Anna certain things are especially distressing like loud noises, crowds, and sometimes the dark. So she has found ways to self-soothe by wearing ear plugs in public places or distracting herself with her game boy.

At age 45 Mary Bauer went on her own to Romania to adopt a child. "I remember vividly the first day or two, I put her on the floor and had these toys I brought and put them around her and she didn't move. I thought, oh my god, she doesn't know how to crawl! This was just the beginning of a long haul of understanding where she was developmentally."

Anna calls her room her condo, a way to indicate her need for some independence and will often spends blocks of time organizing and cleaning it or playing video games, a fairly common hobby for young people on the Autism spectrum.

"As a child I had a hard time socializing with other people," says Anna. "Some of those people who picked on me thought I was weird or mentally unstable. And they called me the R-word, I'm not going to say it because I don't like it, but it means dumb and stupid and to me that's the worst word to listen to." Lately though, she has become more social active, inviting out her church pastor and seeking friends.

Though she was adopted by different parents, Anna has a twin sister also on the spectrum, supporting the generally accepted belief that autism is a genetic disorder. But many site environmental factors including mercury in vaccinations, diet, even heavy rain, as triggers of autism.

Though sensitive to noise and crowds, ironically Anna loves roller coasters, especially the design and color of the cars. "The kind of roller coasters I like are the big, scary kind," says Anna. Who road The Looping Thunder at Oaks Park Amusement Park more than 20 times the day she was there, though she did wear earplugs to avoid the sound of screaming.

Melissa Walsh is 30 years old with Asperger’s Syndrome. Melissa moved from Spokane with her husband Sean after they lost their home to foreclosure. Relocating to Portland, the Walsh’s brought only what they could carry on their backs. For the first few months they lived in a one-bedroom apartment but the $535 rent proved too high and they were forced to leave, making them homeless. “I feel like I disappeared off the face of the earth. I feel like I disappeared when my job did," says Melissa.

During a panic attack, a worker at the food bank comforts Melissa. People with Asperger's crave routine and so homelessness is especially devastating to her. “I’m like a 15-year-old inside, developmentally and emotionally speaking. I feel like a teen with no social skills stuck in an adult body.”

The family of two gets $367 a month in food stamps which they supplement with trips to the food bank.

Melissa takes advantage of Potluck in the Park, which serves free meals on Sundays. At the time of this story, 11.5% of people were out of work in Oregon, making it the third highest unemployment rate in the nation.

Her husband, Sean, 25, suffers from seizures caused by PTSD, the result of an abusive childhood. Prescribed at least 15 different drugs since he was ten, Sean has never been able get his symptoms under control. He estimates that he has $110,000 in unpaid medical bills.

At the Open Door Counseling Center, Melissa and Sean talk to their Mental Health Counselor. The center helps them find a new place to live, coordinates the couple’s doctors, and generally works with navigating day-to-day life.

On a red letter day, Melissa and Sean sign paperwork for their new apartment at the non-profit Join, an organization that helps homeless folks get into permanent housing. Join will pay for their deposit and first month's rent.

Unable to work, Melissa makes about $5 to $10 a day selling newspapers. “All these people pass me by and avoid my eyes. I want to tap them on the shoulder and say, ‘Look at me, I am not invisible.’”

Married after only five weeks, but together for five years, Melissa believes her relationship with Sean has survived the hard times because, “Neither of us can bring ourselves to give up on anything. That is our greatest weakness and our greatest strength. We will not quit.”

Waiting for her Social Security Disability benefits to be approved, Melissa spends her days dreaming of bike shopping, shoes that fit, and a trip to the San Juan Islands, “When you are homeless you have nothing but time.”

Leska Emerald Adams, 51, lives with friend Lynn Szender and her service dog, Orka. Diagnosed with autism in fourth grade, Leska says, “I knew I was different but I didn’t know why or I had no idea HOW different I was. I just knew that everything I wanted socially...to talk to other little kids and play with them, it never happened. It did not happen.” Her symptoms remained mostly manageable until divorce led to an autism regression and subsequent Asperger’s diagnosis almost 40 years later.

In 1980 Leska was first introduced to her Guru, Sri Sri Paramahansa Yogananda, who became the most important thing in her life and for a period of time she wanted to be a nun. Her house is liberally decorated with framed pictures off him, though the majority of the more than 370 she owns are still in storage. Also, for Leska, green is a healing color, to satisfy this love her back yard is filled with trees and both the interior and exterior of her house is painted green.

In 1980 Leska started following Steve Jobs and Apple and developed a bit of an obsession. She estimates that from 1998 until 2002 she spent approximately 16 hours a day on her computer, writing on forums and doing research on Jobs.

“When I first got Orka I was just trying to stay alive. I needed a really big strong dog because I was having trouble walking and doing anything.” Over the last 2 years her health has dramatically improved and now Orka helps keep her mobile.

Her dream is to spend the summers kayaking up the west coast from Puget Sound to Alaska and so regular training with Orka involves swimming, water rescue techniques and kayaking.

“I had a huge amount of bullying and criticism my whole life and it made me want to avoid people. I am really enthusiastic -- I’m full of love and joy and people are a stone wall that gave back constant criticism. I think people are trouble. So with Orka, there’s none of that; people are focused on him so there’s no trouble. I don’t dread going out, taking the bus or any of it because I don’t get the kind of flak I used to. Going out has become really easy because no one is paying any attention to me at all. Every encounter I have now, the focus is on my service dog. Most of the time I don’t have to say a word. People don’t know that I’m socially an idiot."

Leska is a proponent of service dogs for autistic individuals, but warns that training is a monumental commitment. “Your dog will give you what people will never give you. The service dog will give you love, cheer, comfort, loyalty, understanding, some kind of intuitive knowledge that you need help and that you need tasks done, and unconditional gladness to see you and be with you. In every way people fail, the dog succeeds.”

Leska is comfortable being alone, especially with Orka. “I’m a hermit, not social except online. The things I’m really interested in and enthusiastic about grab my focus. Nobody else even cares about the same topics, or cares in the same way or about the same aspects, and nobody seems interested in sharing any of it. So I feel like other people are strange invaders from outer space and there’s nothing in common and it is just endless frustration."

Leska believes that for her, Asperger’s has been a positive condition. “Asperger's might very well have a major part to play in the evolution of mankind. If you look at the last 50 years and the types of people that have advanced mankind the most, they are the crazy out-of-the-box thinkers who stay to themselves, are eccentric, and follow their dreams even though everyone told them it was hogwash. People don’t recognize genius; they don’t recognize visionaries."

Thomas Olrich, 35, was diagnosed with Asperger's four years ago. He also has bipolar disorder (dual diagnosis are not uncommon with Asperger’s) and says he always knew he was different. “I knew something was up. I was always upset, always scared. Something was not clicking.” For Thomas, his Asperger’s presents as anxiety, over stimulation to smells and sounds, and a problem with language and social cues, “I can’t express what I want to say. Sometimes it comes out wrong.”

He says that having a lot of structure, through school, work, and family, has helped him learned to manage the syndrome. Though he has mixed feelings about the DSM getting rid of the term Asperger’s, it won’t change his disability benefits and so he doesn’t think he will be too affected by it. “It’s kind of an unfortunate name,” Thomas says with a laugh.

Thomas says he has daily, “fits” when his anxiety flares up and as he puts it, “My Asperger’s runs away with me a bit.” The fits make him feel anxious, needy and vulnerable and can be caused by anything stress-related, from a school paper, to an over crowded bus ride or even messing up at karaoke.

Thomas has been on and off of pills since he was 18, but says he has faithfully been taking medication for four years with good results.

Thomas says that though he has never had a girlfriend, he is trying to find the right person. “My condition is kind of holding me back. I think it is something that scares off people I like, relationship wise. I don’t know how to do it.” Here Thomas contemplates asking a girl to dance at an event for people with disabilities.

Thomas has worked at the Good Will for about a year, his first real job, where he makes about $360 a month working 15 hours a week. “I feel privileged that I am part of society rather than sitting on my ass not doing anything. It’s great having a job and my own money."

Thomas got his high school diploma is 1995 and now takes Adult Basic Education classes to improve his reading comprehension. For the future he is focused on more adult responsibilities, having a credit card, maybe a better apartment and a computer.

Thomas lives alone in low-income housing, which he pays $562 a month for. He also has a caseworker, Dave, paid through the state (Social Security Disability) who spends around 13 hours a month with Thomas working on community skills, like how to ride public transportation and navigate social situations.

![“My sister, Candice, is the backbone of the family. Our mom and dad would always fight and so she pulled up her pants and became a parent [to me] at age 16. I think that’s why she is so successful and strong. She says she learn](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ca72f4e4b036603e00f5bb/1466635762031-1C1VHG3Z4OQ8QOCTXXOQ/20110718_Thomas_042.jpg)

“My sister, Candice, is the backbone of the family. Our mom and dad would always fight and so she pulled up her pants and became a parent [to me] at age 16. I think that’s why she is so successful and strong. She says she learns things from me all day long, everyday. I just don’t get what she learns.”

“I’m a real human being with a learning disability. I’m human, I make mistakes, but I’ve come so far. Five years ago I was living in squalor and didn’t give a crap about no one. I actually was obsessive and manic. I was a no man, I was greedy and only wanted ‘me-time’. Now, I’m learning about life. I went from a zero to a hero. I had to grow up, but maturity was a bitch for me. Now I’m a big time success story. I used to be scared of failure. But what’s the worst of it? All you can do is try again.”

![“My sister, Candice, is the backbone of the family. Our mom and dad would always fight and so she pulled up her pants and became a parent [to me] at age 16. I think that’s why she is so successful and strong. She says she learn](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ca72f4e4b036603e00f5bb/1466635762031-1C1VHG3Z4OQ8QOCTXXOQ/20110718_Thomas_042.jpg)

When you ask 11-year-old Willie Rates about life with Asperger’s he seems comfortable with his place in the world, both figuratively and literally. “Well, you’re indeed not usual, which I’m perfectly ok with. It’s like I’m Portland unusual, or Los Angeles unusual.” A lover of ancient Egypt & Rome, dinosaurs, and Playmobil figures, Willie will tell you that first and foremost he is a filmmaker, with exactly 123 movies to his credit.

He lives in Portland, Oregon with his Mother Tobi, Father Dale, and his 7-year-old brother Jacob, who is also on the Autism spectrum. It was more than two years ago that Willie first donned his now trademark Nemes, a striped headcloth worn by pharaohs in ancient Egypt. The remnants of a Halloween costume, it is a visual reminder of his obsession with Ancient Egypt.

Willie morphed his interests in ancient Egypt and dinosaurs to create his own, the Phananosaraptorosaurus (Species: Marinus Subspecies: Domesticus) which he imitates by walking on his hands at home and in public. “I remember right before fifth grade, Willie asked me if he had to walk bipedally at school or if he could walk quadrupedally,” says his mother.

An avid stop motion filmmaker, Willie movie's are distributed through his production company, KhAnubis Productions. His film topics usually center on ancient Rome and Egypt, with Playmobil figures or stuffed animals taking the starring roles. His latest piece, Dr. Tyrannus’ Revenge, is complete with German Subtitles.

Like many preadolescents, Willie reluctantly does a little grooming before school. Though Tobi and Dale are not on the autism spectrum, Tobi has a twin sister who children are, laying credence to the generally accepted belief that autism is a genetic disorder. Tobi agrees, “I would say for me and Dale, we’re not autistic, but we definitely see similarities in ourselves, just not enough to make a diagnosis. Though,” she jokes, “usually if your kid’s been diagnosed, you should probably get a diagnosis yourself!” The truth is, there is no one certain cause for autism because autism is not a medical condition. Instead, it is a definition given to those that exhibit a specific set of behaviors.

“In comparison to my last school, it’s a paradise,” says Willie. “You can customize your own schedule, you actually get to say whatever you want. They’re much nicer at Pacific Crest and there are a lot less kids so I don’t have to make as much friends to be popular at the school. I now think I’m the kind of guy who has a lot of friends."

During math class, Willie’s notebook fills up with drawings rather than equations. In general his relationship with school is uneven, with him excelling in topics that fascinate him. Like many people that have Asperger’s, Willie can spend hours fixated on very specific topics or interests, which is why many with the diagnosis make good lawyers or computer programmers. “To us, Willie was our first child, the quirks we noticed with him, we just thought he was a genius. But the teacher at the preschool we went to, she suggested we get him evaluated,” say his mother.

Here, Willie creates a movie set.

Willie attempts to play with his brother Jacob. Jacob is profoundly autistic and for the most part, nonverbal, though he can sign some words.

His father, Dale, marvels at the changes time has brought, “In my day, in the 60’s, there was one description, or two descriptions really, retarded or normal. And you didn’t want to be retarded. Now it’s not a shame. It’s everywhere. We’re all a little weird everywhere you look. Everyone’s got a quirk, or a strange little thing. And that’s ok, that’s what makes us unique. Otherwise we’re just robots and rocks.”

We’re a happy group here,” says Dale. “We have group hugs, actually we have a family hug time. I mean it’s not like it’s scheduled, it just happens. Very few things are scheduled around here actually.”

First tested for Autism at age 4, Willie’s path to a diagnosis hasn’t been a straightforward one, “First we were told, we don’t what, but there is something going on here,” says his father. “And that turned into Autism and that sort of started becoming Asperger's and then it became…who knows he might just be a really unique guy.”

E.A. is a mother, wife, ballet dancer, public speaker, and self advocate. She says that she has spent most of her life pretending to be normal. “Nothing has come naturally to me other than my intuition. But everything else I do, my mannerisms, the way that I talk, the faces that I make, the things that I do, how I do them have all had to be learned and have all had to run through my internal editor. This is so that they can be compatible with what I am showing or what I am doing so that I am not detected by the citizens of this world as different.”

"In my next life I want to be born messy!" laughs E.A. as she picks up leaves off her yard one by one.

"To be misunderstood is extremely frustrating and it happens to me on a daily basis. I’m frustrated that I have to do this on a daily basis and then field off questions like, ‘But you seem so normal’ or ‘You seem fine.'"

“I have a certain way that I get ready every day. If I’m going to clean my house, there is a certain way it needs to be clean and a certain way it needs to be done. The was I do it is very scripted because that is the only way I know how to do it.” People with Asperger's are often comforted by routine.

E.A. says she often has difficulty reading facial expressions and social situations, a trait common in Asperger's. This is true even for her husband and children.

E.A.'s youngest son is on the autism spectrum and she works hard to make sure he doesn't make the same mistakes she did, often correcting his behavior. "That’s what I’m looking for, to help him increase his recovery time, between upsets, as quickly as possible, so that the damage to self-esteem is minimized."

E.A. is the Community Council Chair and Research Assistant at Academic Autistic Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE). She also does a lot of work with disabilty rights, “My goal in public speaking and advocacy work is to bring a sense of reality into the picture, a sense of first hand experience, and hopefully, a large sense of truth.”

E.A. has a cochlear implant and hearing aid and says that in some ways it has been a blessing in disguise because she is so sensitive to noise.

“When I was younger I would decide somebody was my friend and that was it in my head, we were friends and we didn’t have to go through all those formalities and rules that I didn’t even know existed. So I would be way too forward and come on way too strong and just be so hurt when this person didn’t want to be my friend."

E.A. finds solace in one of her passions, ballet, and will spend hours at practice. “What I like about dance is that it is a form of expression without having to speak. Things might be stressful at work or certain things could be happening in life, but there’s always ballet class, there’s always that barre, and that leotard and those tights that I put on. And when I go in there my mind goes to a completely different place and it becomes a form of expression where I am not having to speak or interpret anything...as long as I can get the choreography down!”

“I don’t need to be fixed and I don’t need to be cured and I wouldn’t want to be fixed or cured. I want to be accommodated, I want to be respected and I want to be understood.”

"When I was younger I wasn't always accepting of myself and I wanted to be normal. A lot of times I look at other people and I think, I wish I could be that person," say Anna Bauer who lives with her mother Mary. Diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome, Anna had a difficult childhood, often bullied for being different. Now 22-years-old, her mother Mary is not sure what lies ahead for her daughter who has never had a job and still lives at home.

After a stressful move from her childhood home, Anna Bauer lays on her prized possession, a 24-second shot clock, to comfort herself. Because of her Asperger's Anna has a tendency to fixate on certain subjects or objects. For her it is scoreboards, roller coasters, and most importantly, shot clocks, of which purchased two on ebay for around $700.

Anna moves her 30-pound shot clock. When she and her mother go on road trips the shot clock comes with and Anna now has planned a visit to University of California, Berkeley to visit the scoreboard they have there. "Ever since I go this shot clock, especially when I am home alone, I feel less lonely and I feel like it is another friend to me and it actually gives me company," say Anna.

Anna volunteers as a scoreboard operator at the Beaverton Hoop and last year received the volunteer of the year award. Originally fascinated with gym floors, she would lie on for hours. Now she moved on to score boards and dreams of being a professional score keeper.

Anna started attending the local community Church, much to the surprise of her Atheist mother. "I like going to church," say Anna. "Where it is peaceful and positive, and the people there are really nice."

For Anna certain things are especially distressing like loud noises, crowds, and sometimes the dark. So she has found ways to self-soothe by wearing ear plugs in public places or distracting herself with her game boy.

At age 45 Mary Bauer went on her own to Romania to adopt a child. "I remember vividly the first day or two, I put her on the floor and had these toys I brought and put them around her and she didn't move. I thought, oh my god, she doesn't know how to crawl! This was just the beginning of a long haul of understanding where she was developmentally."

Anna calls her room her condo, a way to indicate her need for some independence and will often spends blocks of time organizing and cleaning it or playing video games, a fairly common hobby for young people on the Autism spectrum.

"As a child I had a hard time socializing with other people," says Anna. "Some of those people who picked on me thought I was weird or mentally unstable. And they called me the R-word, I'm not going to say it because I don't like it, but it means dumb and stupid and to me that's the worst word to listen to." Lately though, she has become more social active, inviting out her church pastor and seeking friends.

Though she was adopted by different parents, Anna has a twin sister also on the spectrum, supporting the generally accepted belief that autism is a genetic disorder. But many site environmental factors including mercury in vaccinations, diet, even heavy rain, as triggers of autism.

Though sensitive to noise and crowds, ironically Anna loves roller coasters, especially the design and color of the cars. "The kind of roller coasters I like are the big, scary kind," says Anna. Who road The Looping Thunder at Oaks Park Amusement Park more than 20 times the day she was there, though she did wear earplugs to avoid the sound of screaming.

Melissa Walsh is 30 years old with Asperger’s Syndrome. Melissa moved from Spokane with her husband Sean after they lost their home to foreclosure. Relocating to Portland, the Walsh’s brought only what they could carry on their backs. For the first few months they lived in a one-bedroom apartment but the $535 rent proved too high and they were forced to leave, making them homeless. “I feel like I disappeared off the face of the earth. I feel like I disappeared when my job did," says Melissa.

During a panic attack, a worker at the food bank comforts Melissa. People with Asperger's crave routine and so homelessness is especially devastating to her. “I’m like a 15-year-old inside, developmentally and emotionally speaking. I feel like a teen with no social skills stuck in an adult body.”

The family of two gets $367 a month in food stamps which they supplement with trips to the food bank.

Melissa takes advantage of Potluck in the Park, which serves free meals on Sundays. At the time of this story, 11.5% of people were out of work in Oregon, making it the third highest unemployment rate in the nation.

Her husband, Sean, 25, suffers from seizures caused by PTSD, the result of an abusive childhood. Prescribed at least 15 different drugs since he was ten, Sean has never been able get his symptoms under control. He estimates that he has $110,000 in unpaid medical bills.

At the Open Door Counseling Center, Melissa and Sean talk to their Mental Health Counselor. The center helps them find a new place to live, coordinates the couple’s doctors, and generally works with navigating day-to-day life.

On a red letter day, Melissa and Sean sign paperwork for their new apartment at the non-profit Join, an organization that helps homeless folks get into permanent housing. Join will pay for their deposit and first month's rent.

Unable to work, Melissa makes about $5 to $10 a day selling newspapers. “All these people pass me by and avoid my eyes. I want to tap them on the shoulder and say, ‘Look at me, I am not invisible.’”

Married after only five weeks, but together for five years, Melissa believes her relationship with Sean has survived the hard times because, “Neither of us can bring ourselves to give up on anything. That is our greatest weakness and our greatest strength. We will not quit.”

Waiting for her Social Security Disability benefits to be approved, Melissa spends her days dreaming of bike shopping, shoes that fit, and a trip to the San Juan Islands, “When you are homeless you have nothing but time.”

Leska Emerald Adams, 51, lives with friend Lynn Szender and her service dog, Orka. Diagnosed with autism in fourth grade, Leska says, “I knew I was different but I didn’t know why or I had no idea HOW different I was. I just knew that everything I wanted socially...to talk to other little kids and play with them, it never happened. It did not happen.” Her symptoms remained mostly manageable until divorce led to an autism regression and subsequent Asperger’s diagnosis almost 40 years later.

In 1980 Leska was first introduced to her Guru, Sri Sri Paramahansa Yogananda, who became the most important thing in her life and for a period of time she wanted to be a nun. Her house is liberally decorated with framed pictures off him, though the majority of the more than 370 she owns are still in storage. Also, for Leska, green is a healing color, to satisfy this love her back yard is filled with trees and both the interior and exterior of her house is painted green.

In 1980 Leska started following Steve Jobs and Apple and developed a bit of an obsession. She estimates that from 1998 until 2002 she spent approximately 16 hours a day on her computer, writing on forums and doing research on Jobs.

“When I first got Orka I was just trying to stay alive. I needed a really big strong dog because I was having trouble walking and doing anything.” Over the last 2 years her health has dramatically improved and now Orka helps keep her mobile.

Her dream is to spend the summers kayaking up the west coast from Puget Sound to Alaska and so regular training with Orka involves swimming, water rescue techniques and kayaking.

“I had a huge amount of bullying and criticism my whole life and it made me want to avoid people. I am really enthusiastic -- I’m full of love and joy and people are a stone wall that gave back constant criticism. I think people are trouble. So with Orka, there’s none of that; people are focused on him so there’s no trouble. I don’t dread going out, taking the bus or any of it because I don’t get the kind of flak I used to. Going out has become really easy because no one is paying any attention to me at all. Every encounter I have now, the focus is on my service dog. Most of the time I don’t have to say a word. People don’t know that I’m socially an idiot."

Leska is a proponent of service dogs for autistic individuals, but warns that training is a monumental commitment. “Your dog will give you what people will never give you. The service dog will give you love, cheer, comfort, loyalty, understanding, some kind of intuitive knowledge that you need help and that you need tasks done, and unconditional gladness to see you and be with you. In every way people fail, the dog succeeds.”

Leska is comfortable being alone, especially with Orka. “I’m a hermit, not social except online. The things I’m really interested in and enthusiastic about grab my focus. Nobody else even cares about the same topics, or cares in the same way or about the same aspects, and nobody seems interested in sharing any of it. So I feel like other people are strange invaders from outer space and there’s nothing in common and it is just endless frustration."

Leska believes that for her, Asperger’s has been a positive condition. “Asperger's might very well have a major part to play in the evolution of mankind. If you look at the last 50 years and the types of people that have advanced mankind the most, they are the crazy out-of-the-box thinkers who stay to themselves, are eccentric, and follow their dreams even though everyone told them it was hogwash. People don’t recognize genius; they don’t recognize visionaries."

Thomas Olrich, 35, was diagnosed with Asperger's four years ago. He also has bipolar disorder (dual diagnosis are not uncommon with Asperger’s) and says he always knew he was different. “I knew something was up. I was always upset, always scared. Something was not clicking.” For Thomas, his Asperger’s presents as anxiety, over stimulation to smells and sounds, and a problem with language and social cues, “I can’t express what I want to say. Sometimes it comes out wrong.”

He says that having a lot of structure, through school, work, and family, has helped him learned to manage the syndrome. Though he has mixed feelings about the DSM getting rid of the term Asperger’s, it won’t change his disability benefits and so he doesn’t think he will be too affected by it. “It’s kind of an unfortunate name,” Thomas says with a laugh.

Thomas says he has daily, “fits” when his anxiety flares up and as he puts it, “My Asperger’s runs away with me a bit.” The fits make him feel anxious, needy and vulnerable and can be caused by anything stress-related, from a school paper, to an over crowded bus ride or even messing up at karaoke.

Thomas has been on and off of pills since he was 18, but says he has faithfully been taking medication for four years with good results.

Thomas says that though he has never had a girlfriend, he is trying to find the right person. “My condition is kind of holding me back. I think it is something that scares off people I like, relationship wise. I don’t know how to do it.” Here Thomas contemplates asking a girl to dance at an event for people with disabilities.

Thomas has worked at the Good Will for about a year, his first real job, where he makes about $360 a month working 15 hours a week. “I feel privileged that I am part of society rather than sitting on my ass not doing anything. It’s great having a job and my own money."

Thomas got his high school diploma is 1995 and now takes Adult Basic Education classes to improve his reading comprehension. For the future he is focused on more adult responsibilities, having a credit card, maybe a better apartment and a computer.

Thomas lives alone in low-income housing, which he pays $562 a month for. He also has a caseworker, Dave, paid through the state (Social Security Disability) who spends around 13 hours a month with Thomas working on community skills, like how to ride public transportation and navigate social situations.

“My sister, Candice, is the backbone of the family. Our mom and dad would always fight and so she pulled up her pants and became a parent [to me] at age 16. I think that’s why she is so successful and strong. She says she learns things from me all day long, everyday. I just don’t get what she learns.”

“I’m a real human being with a learning disability. I’m human, I make mistakes, but I’ve come so far. Five years ago I was living in squalor and didn’t give a crap about no one. I actually was obsessive and manic. I was a no man, I was greedy and only wanted ‘me-time’. Now, I’m learning about life. I went from a zero to a hero. I had to grow up, but maturity was a bitch for me. Now I’m a big time success story. I used to be scared of failure. But what’s the worst of it? All you can do is try again.”