“This job is mentally challenging, and you get a lot of criticism. I’m not here to make friends. I’m here to save lives.”—Jennifer Parker

Most hospital nurses work a specific territory: one unit in the facility, one slot in a sprawling hierarchy of caregivers. Not Jennifer Parker. The 40-year-old Legacy Emanuel nurse describes her job as “putting out fires wherever they happen.” She’s one of the hospital’s handful of trauma and critical care response nurses, a position Emanuel developed to keep its operation afloat through sometimes-crazy evenings and nights.

The Legacy Trauma Unit treats a female gunshot-wound victim. Damage to her liver and bowel complicates the three-hour surgery.

“Her leg might never be the same,” says Parker, who helps coordinate an effort that involves as many as 12 doctors, nurses, and technicians at a time.

On a Friday night, a family passes time in the ER’s waiting room, eager for news. In one year the hospital’s emergency department treats about 40,000 patients—around 110 per day.

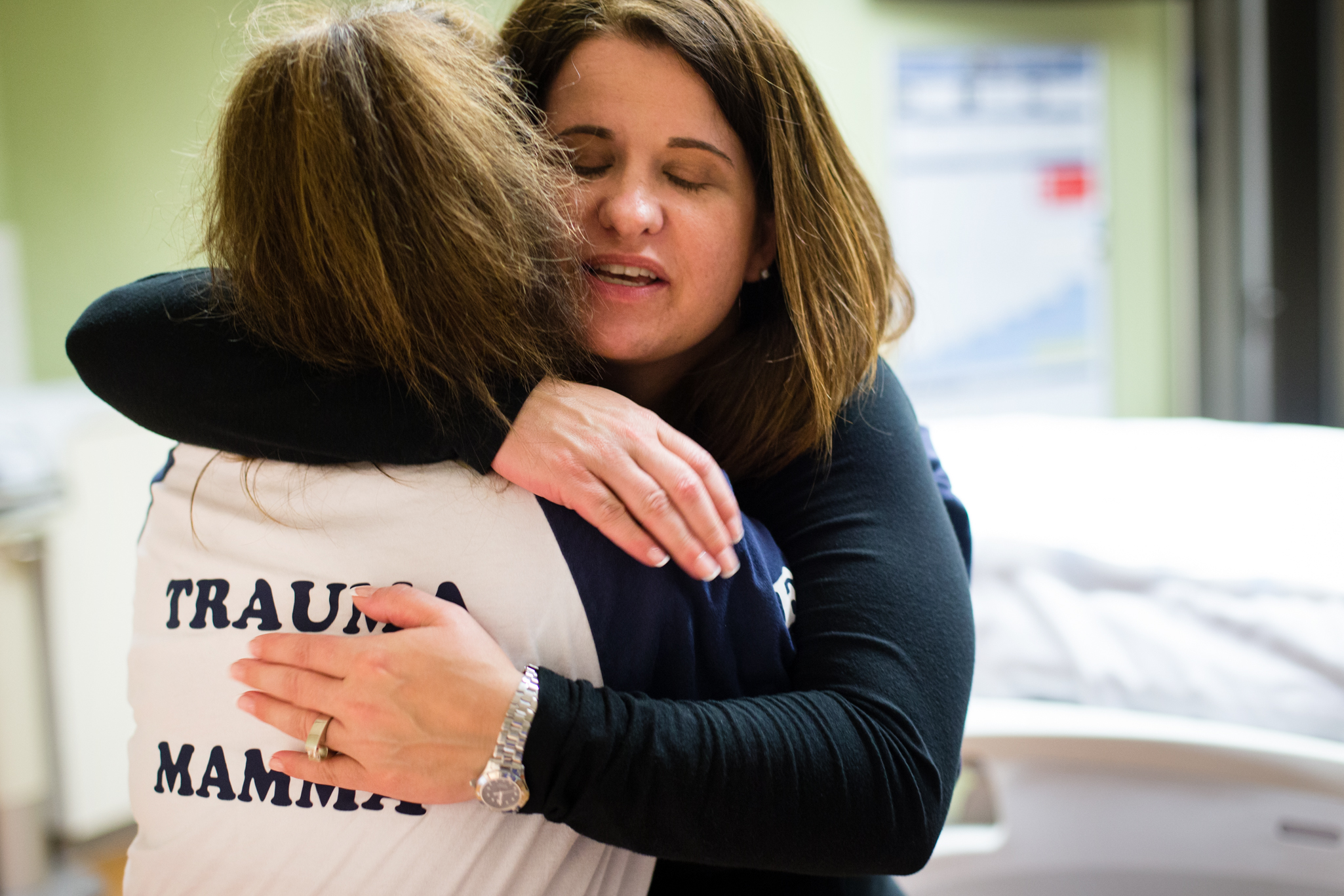

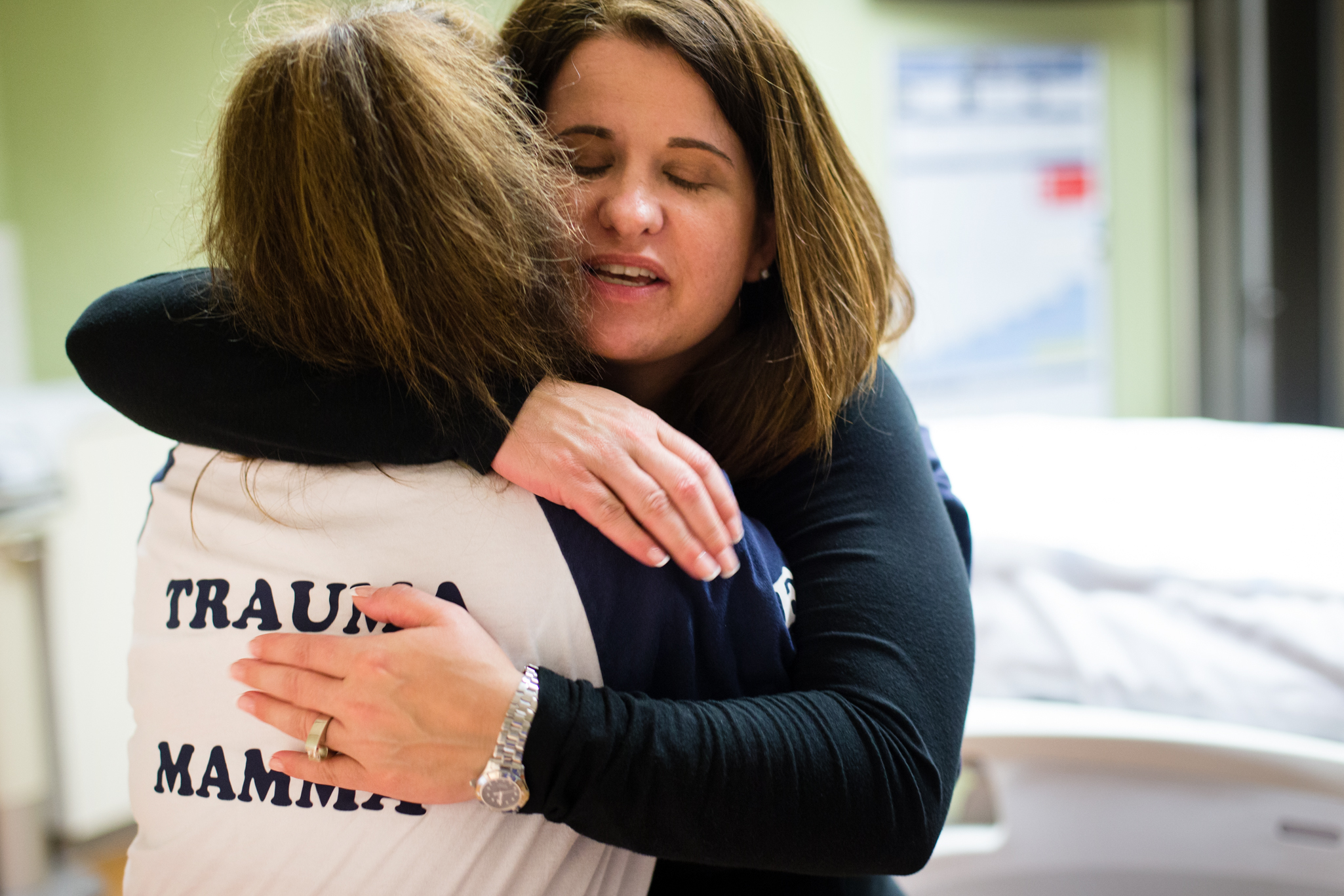

Parker hugs fellow nurse Karyn McComb whose shirt reads, Trauma Mamma.

During her shifts, Parker tracks critical cases all the way from the North Portland hospital’s emergency room to its operating tables to its ICU. As patients move from one team of specialists to another, Parker stays with them, managing the transitions, relaying critical information, and providing hands-on care.

“NOW STOP THAT. Stop acting like a child. You want this to look pretty don’t you?” Intermediately gruff and soothing, Parker contends with a female patient who requires stitches after suffering a facial laceration from being hit by a car. The intoxicated patient struggles so much, restraints are required. “It took three of us to do a repair a 3-year-old should have been able to handle,” Parker says.

Beyond training, a steady nerve, flexibility, and a sense of humor are mandatory. “All I know when I show up is that I’m getting my pager and clocking in,” Parker says. “I think that’s the attraction: the job’s diversity. I could be mopping a floor, or trying to keep someone’s heart beating.”

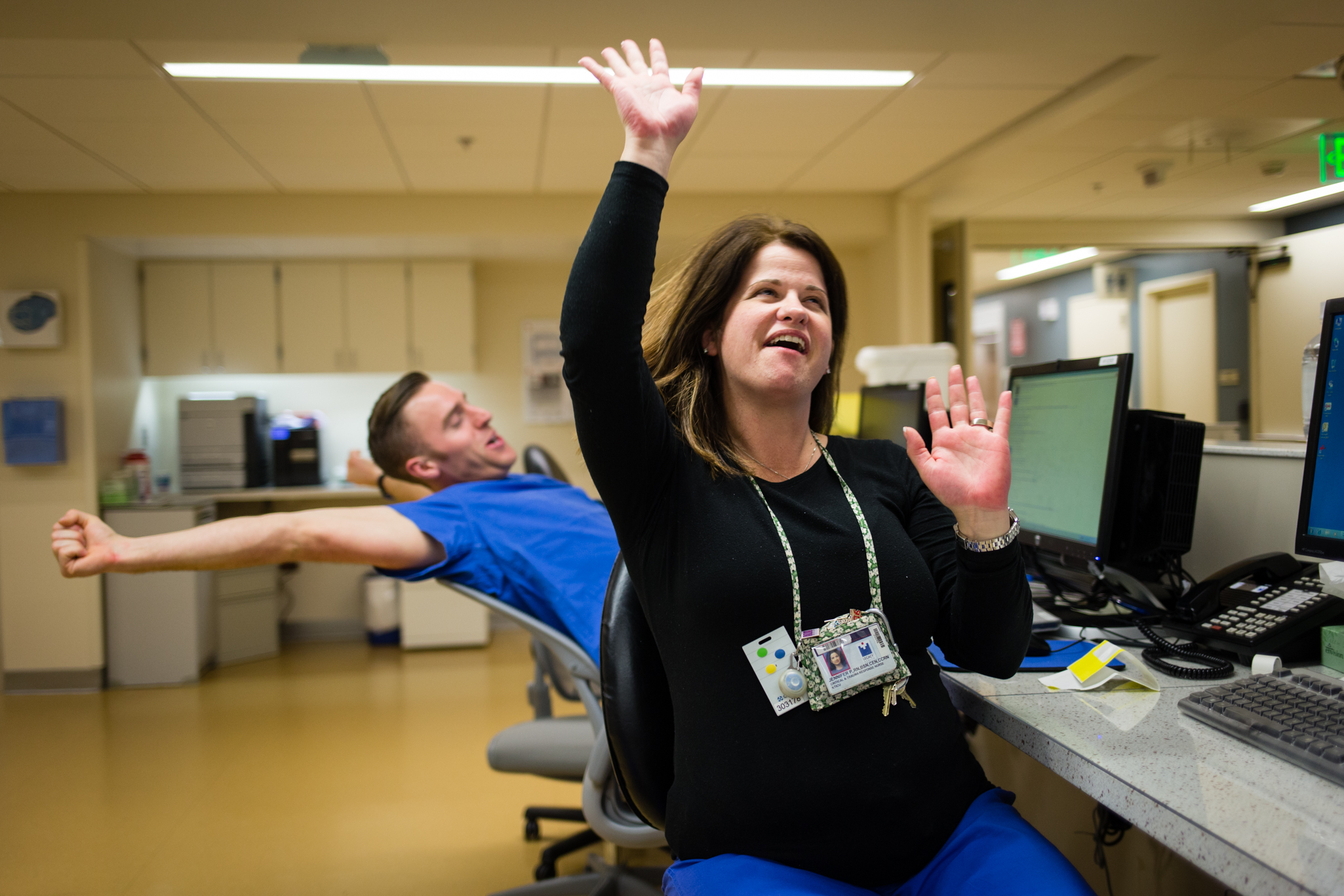

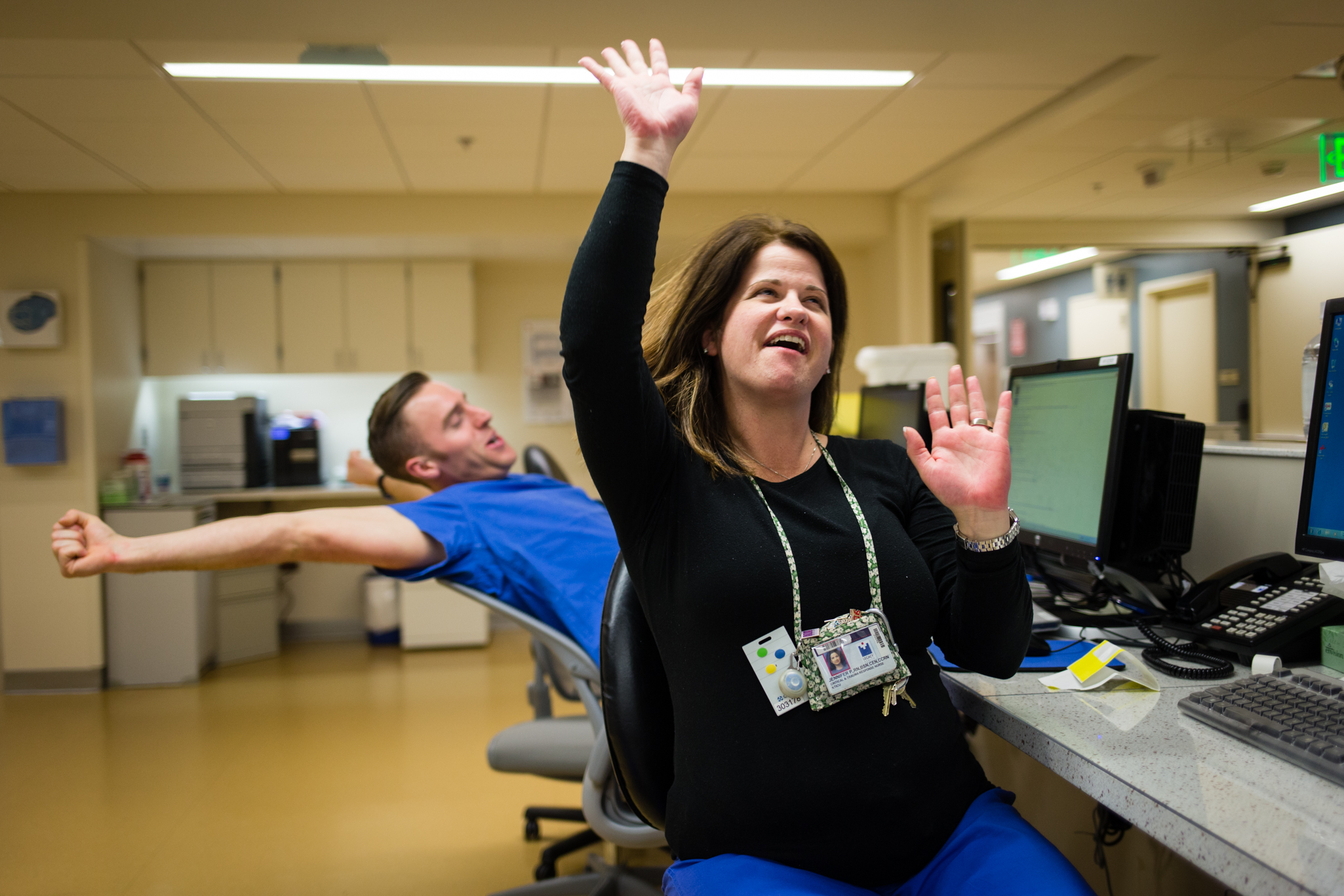

Parker celebrates when she checks the clock and sees her shift ends in 15 minutes. Her typical week includes three 12-hour shifts from 3 p.m. to 3 a.m. She says adrenaline makes transitioning out of shifts difficult. (She relaxes during her drive home.)

“People do die, no matter what you do,” says William Long, Legacy’s medical director of trauma services. “You need someone who doesn’t get rattled.”

“This job is mentally challenging, and you get a lot of criticism. I’m not here to make friends. I’m here to save lives.”—Jennifer Parker

Most hospital nurses work a specific territory: one unit in the facility, one slot in a sprawling hierarchy of caregivers. Not Jennifer Parker. The 40-year-old Legacy Emanuel nurse describes her job as “putting out fires wherever they happen.” She’s one of the hospital’s handful of trauma and critical care response nurses, a position Emanuel developed to keep its operation afloat through sometimes-crazy evenings and nights.

The Legacy Trauma Unit treats a female gunshot-wound victim. Damage to her liver and bowel complicates the three-hour surgery.

“Her leg might never be the same,” says Parker, who helps coordinate an effort that involves as many as 12 doctors, nurses, and technicians at a time.

On a Friday night, a family passes time in the ER’s waiting room, eager for news. In one year the hospital’s emergency department treats about 40,000 patients—around 110 per day.

Parker hugs fellow nurse Karyn McComb whose shirt reads, Trauma Mamma.

During her shifts, Parker tracks critical cases all the way from the North Portland hospital’s emergency room to its operating tables to its ICU. As patients move from one team of specialists to another, Parker stays with them, managing the transitions, relaying critical information, and providing hands-on care.

“NOW STOP THAT. Stop acting like a child. You want this to look pretty don’t you?” Intermediately gruff and soothing, Parker contends with a female patient who requires stitches after suffering a facial laceration from being hit by a car. The intoxicated patient struggles so much, restraints are required. “It took three of us to do a repair a 3-year-old should have been able to handle,” Parker says.

Beyond training, a steady nerve, flexibility, and a sense of humor are mandatory. “All I know when I show up is that I’m getting my pager and clocking in,” Parker says. “I think that’s the attraction: the job’s diversity. I could be mopping a floor, or trying to keep someone’s heart beating.”

Parker celebrates when she checks the clock and sees her shift ends in 15 minutes. Her typical week includes three 12-hour shifts from 3 p.m. to 3 a.m. She says adrenaline makes transitioning out of shifts difficult. (She relaxes during her drive home.)

“People do die, no matter what you do,” says William Long, Legacy’s medical director of trauma services. “You need someone who doesn’t get rattled.”